NEVER SAY "NEVER!"

or: How I celebrated my 60th Birthday by finally becoming a Bat Mitzvah, 47 years late!

My life hasn’t always progressed along the “normal” trajectory, and for young people who are suffering due to circumstances out of their control (like a worldwide pandemic that disrupted their schooling and socialization) I think that can be very valuable thing to hear.

There are many examples I could give you, but today I’m going to focus on the story of why I didn’t become a Bat Mitzvah at 13, as is traditional, but rather did so on my 60th Hebrew birthday this past weekend. More on that to come below in my D’var Torah.

This past shabbat was a special one, Zachor, which falls the shabbat immediately preceding the festival of Purim (which begins tonight at sundown). I read the maftir and haftorah, which used to not be allowed for women, and still isn’t in depending on where one worships. My levels of observance have been all over the map, but I’m a member of an egalitarian conservative synagogue, because it is where I feel most comfortable at this point in my life.

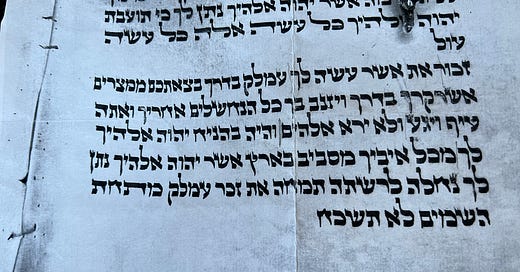

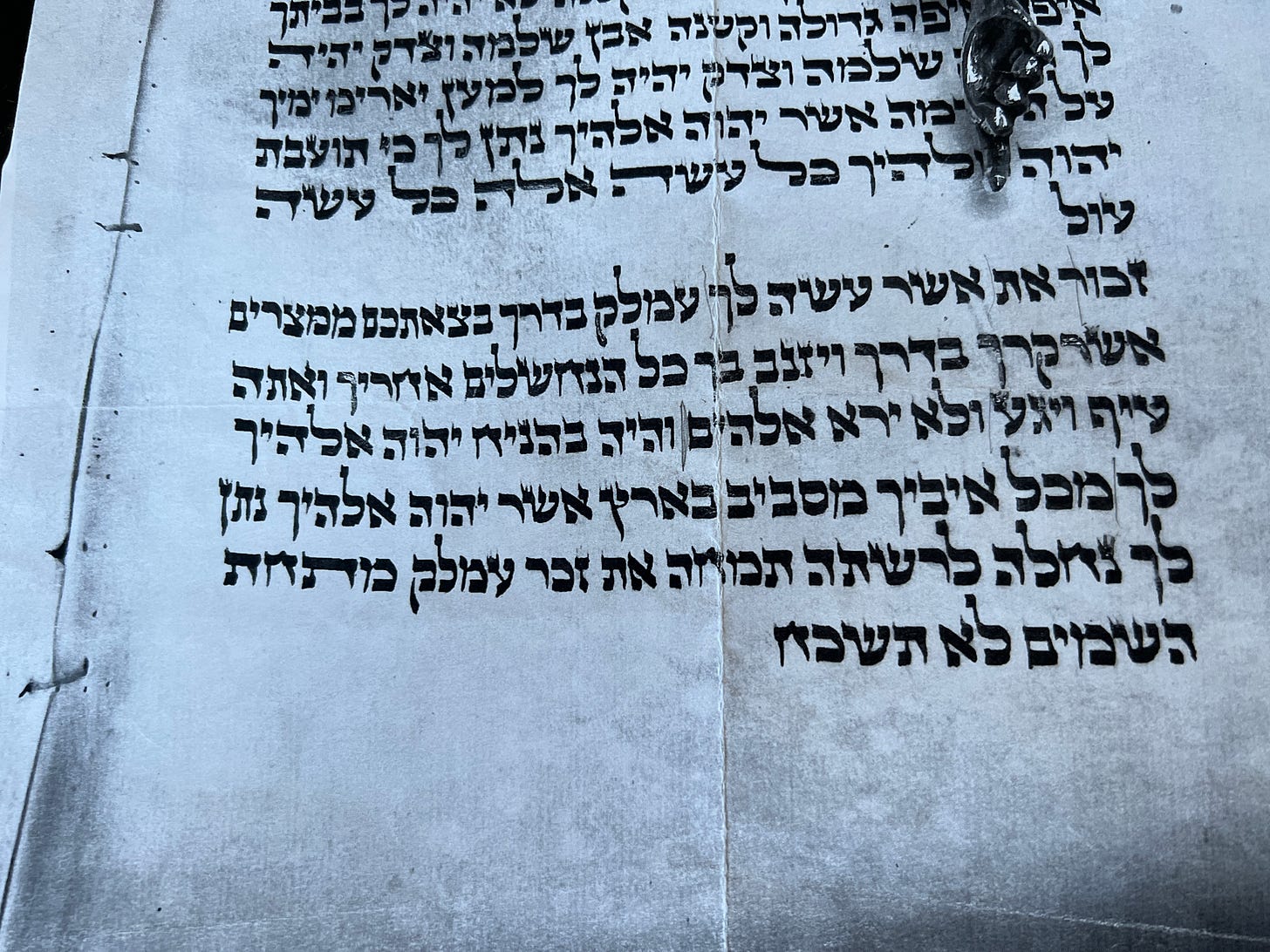

Because it was a special shabbat, I had the especially meaningful honor of reading from one of the 1564 Czech memorial scrolls that were rescued the year after I was born thanks to the generosity of Ralph Yablon, who donated them to the Westminster Synagogue in London, where they were restored and then sent out to congregations around the world - one of which is ours. From the Westminster synagogue website:

“As an intimate link with individual congregations that were destroyed by the Nazis, the rescued Scrolls are a symbol of sorrow but also of hope as they are read and used, becoming part of the many communities, Museums and Educational Establishments around the World.”

My haftorah was from the prophet Samuel (1:15), and I have a LOT OF THOUGHTS AND FEELS about it. And that’s a good thing, because after the readings, the Bat Mitzvah gives what is called a D’Var Torah, or a word of Torah. This is where one gives an original analysis, synthesizing the ideas in the text, previous writings on it, and the insights that you’ve developed as a result of your study.

Talk about a perfect assignment for a 60-year-old Jewish nerd like me…

And so, without further ado, I give you my d’var torah.

D’Var Torah – Zachor 3 4 23

“Today I am a woman.”

Thank you for joining me today on my 60th Hebrew birthday, as I finally become a Bat Mitzvah.

This was all supposed to happen back in 1976. The date was booked at the West London Synagogue and I’d started learning my portion. But in 1975, we moved back to the US – a move I wasn’t happy about, especially coming at one of the most awkward times of adolescence – junior high.

So, I refused to become a bat mitzvah, much to my parents’ chagrin.

In 2019, I joined an adult bnei mitzvah class at Temple Beth El in Stamford, and planned to be a part of a group service there. But then Covid struck, and we moved further up the coast, so…that didn’t happen either.

You know what they say, third time lucky! I’m grateful to be surrounded by friends and family for this 47-years past-due simcha. Thank you, Rabbi W and especially Cissi my wonderful tutor, for helping me to get here. Thank you, Brendan for lending your beautiful voice to the service, and for your inspirational journey to becoming an adult Bar Mitzvah last year. A special thank you to my children, and my husband, for supporting their wife and mother’s meshugenah idea, and to my wider family for setting an example that age is not a barrier. My late grandmother, Dorothy, graduated from Fordham University in 1984, the same year I graduated from Duke. She was 80 years old. We were both awarded diplomas, but Grandma got a standing ovation with hers. The yad I used to read maftir was given to my late great-uncle Sidney by his medical partners when he re-celebrated his bar mitzvah for his 85th birthday. Just last week, my cousin David celebrated his 75th birthday by reading his Bar Mitzvah portion. So, to the younger people in the room – it’s never too late!

My only regret about not doing this earlier is that my parents, Susan and Stanley Darer, of Blessed Memory, aren’t here to see the last of their three children finally become a Bat Mitzvah. But I feel their presence here today.

Now for the d’var torah. To say that this week’s maftir and haftorah gives us food for thought is an understatement. I could talk about it for hours, but don’t worry – I won’t, because there’s a delicious kiddush and lunch waiting for us after the service.

I’ve often spoken about how as a writer I love to explore the grey areas of human existence, because it forces me to think about questions where there isn’t a clear-cut answer.

That’s why Judaism is the perfect faith for me. As we often joke, you put two Jewish people in a room, and you end up with three opinions.

I was texting with my cousin Rob about writing this dvar torah, and he pointed out that the maftir presents a paradox. G-d tells us to blot out the memory of Amalek, but at the same time to remember him. These paradoxical instructions are of such important that they comprise three of the 613 mitzvot compiled by the Rambam, Maimonides.

We also read this passage not just once, but twice every year; once during the sequential reading of Deuteronomy, but also on the shabbat before Purim, the festival that falls this Tuesday, my other 60th birthday. Purim celebrates our deliverance from destruction at the hands of Haman, reportedly a descendant of Amalek.

This shabbat is named after the first word of the maftir: ZACHOR – “REMEMBER”, a word that is engraved on the Ner Tamid, the eternal light hanging above the ark behind me.

The command to remember is a central part of our faith. In “Zakhor: Jewish History and Jewish Memory,” the late historian Yosef Haim Yerushalmi noted that zachor is repeated nearly 200 times in the Tanakh. He suggests that this commandment to remember has been central to the preservation of our faith over several millennia of dispersion, persecution, and ultimately, renewal.[1]

As the late Jonathan Sacks, the chief rabbi of the United Kingdom observed:

We are … joined vertically to those who came before us, whose story we make our own. To be a Jew is to be a link in the chain of the generations, a character in a drama that began long before we were born and will continue long after our death. Memory is essential to identity – so Judaism insists … To be a Jew is to know that the history of our people lives on in us.[2]

That’s one of the reasons I decided to finally become a Bat Mitzvah at 60.

When we go to the social hall, you’ll see a collage of some family members who became Bnei Mitzvah before me, from my grandfather Murray and his siblings to my sister and brother to my son and my nephew, and my many, many cousins. L’Dor V’dor, from generation to generation.

But now for a true confession: I find Haftorah Zachor deeply disturbing.

To recap, Samuel tells King Saul that G-d has commanded him to seek revenge upon the Amalekites for the sneak attack they made on the weak and vulnerable during the Exodus from Egypt: “Now go attack Amalek, and proscribe all that belongs to him. Spare no one, but kill alike men and women, infants and sucklings, oxen and sheep, camels and asses!”

Killing everyone because they are members of a certain group…Who am I to question G-d, but doesn’t that sound a lot like genocide?

The good news is that I’m not alone in my disquiet. Rabbinic commentators through the ages have struggled with this command and as you can imagine there are many, many interpretations of what this instruction means.

Those of you who know my research geek tendencies won’t be at all surprised when I tell you that I’ve probably spent a LOT more time than your average 13-year-old reading different rabbinic and scholarly interpretations. In the interest of brevity, I’m not going to list them all, but rather explain my takeaway from these troubling commands.

In the Haftorah Saul obeys most Samuel’s genocidal command, but he spares the Amalekite King, Agag and the choice livestock. He has no problem killing all the people, but spares the king and the cattle? What’s that all about?

When Samuel calls Saul out on his failure to kill everyone and everything associated with Amalek, Saul claims that the soldiers took the livestock to “sacrifice to the Lord your G-d at Gilgal”. He’s the King and military leader, but he blames things on his troops, rather than taking responsibility. His response also has echoes of the second of the four children at the Passover seder: the one called “evil” in the Haggadah we used when I was a kid, but revised to ‘skeptical’ in more up to date versions. Why? Because he refers to “YOUR” G-d, not “OUR G-d.”[3] Was Saul, like me, skeptical about humans who style themselves as prophets?

I think a healthy dose of skepticism is a sign of intelligence rather than evil, as long as it doesn’t descend into nihilism. Without skepticism, we wouldn’t have scientific breakthroughs. Methodic doubt is a tool for thinking critically. I don’t fault Saul for that. What I do fault him for is refusing to hold himself accountable for his decisions, and for blaming others. That’s poor leadership, and it’s something we see all too often in public life – and if we’re honest, in our own lives, too.

I simply can’t accept the dangerous idea that all members of any group are evil and incapable of redemption, and thus need to be annihilated. We know where it leads – many of us in this room have gaps in our family trees because the Nazis espoused such ideology. My paternal great-grandparents, Chaim and Fayge Darer, were murdered in Ukraine as a result of it.

But another thing I struggle with is Samuel’s insistence on unquestioning obedience. It reminds me too much of how authoritarian religious and political leaders throughout history, including in our present day, have used interpretations of “G-d’s command” to encourage hatred of others so they can gain and hold onto power. It also evokes echoes of the “I was just obeying orders” defense at Nuremberg.

More than that, blind obedience negates free will, which is the essence of our humanity. Abraham, the shared forefather of three faiths, Judaism, Islam and Christianity, argued directly with G-d, as did Moses, thereby modeling a relationship with the divine that allows us to question divine wisdom in our fight for justice and righteousness.

Saul, on the other hand, received his orders through Samuel – a prophet, to be sure, but like all humans, one that contained both the yetzer tov – the inclination to do good— and the yetzer hara, the inclination to do evil. History has shown us how “divine word” can be twisted by human interpretation with decidedly ungodly results. Just look at how the concept of “civilizing the natives” was used to justify enslavement and colonization by empires around the world. Here in the United States, Manifest Destiny, the concept that due to their inherent superiority, white European Americans were divinely ordained to settle the entire continent of North America, was used to justifiy extreme measures against the indigenous peoples of our land, including forced removal and violent extermination.

We start to see a theme here and that led me to the conclusion that while it’s important to obey the mitzvah of remembering the evil that was done to us by “Amalekites” throughout our history, what we DO with that remembrance is equally important.

That brings me to the second reason I decided to celebrate my Bat Mitzvah at sixty - the process of researching and writing my latest young adult novel Some Kind of Hate against a background of rising antisemitism worldwide. We also see other hatreds on the rise, because as Jake’s mom says in the book: “It never stops with just hating us. Scratch an antisemite and you’ll find a whole bunch of other hatreds, too. People chose to hate the idea of us as a substitute for facing their fears of change in society and the world.”

When we visited Germany in the early 1970’s my dad told me to take off the delicate gold שַׁדַּי necklace I wore all the time – to hide the fact that I was Jewish. My first novel, Confessions of a Closet Catholic, was written to my younger self as a response to the confusing unspoken messages I felt growing up to “Be Jewish, but not TOO Jewish.”

Now, as we see age-old conspiracy theories spreading around the world, I want to stand here on the bimah and say Hineni – here I am, a proud Jewish woman.

The research I did to write the book is a reason that this portion simultaneously repelled and appealed to me – again with the paradox. It included interviewing several former neo Nazis, people whom many of us —including me before I started having those conversations—would consider modern day Amaleks.

The most important thing I learned from those interviews, is that one of the first cracks in their extremist worldview came from being treated with respect and kindness by the people from whom they least deserved it. Learning that changed me – and I’m trying to implement that knowledge into my life and how I deal with people, even those with whom I vehemently disagree.

I haven’t totally mastered it yet. It’s not easy, but nothing truly worthwhile in life ever is. And that’s where I come to my interpretation of the Amalek we need to destroy in every generation. It’s the tendency to hate within ourselves.

Yes, we must remember what was done to us - Zachor! But the internal Amalek we must fight is using our own trauma as a justification to inflict trauma on others. We cannot use “Zachor” as a call for continuing the cycle of hatred.

Which brings me back to paradoxes. Parker Palmer wrote in The Courage to Teach “The poles of a paradox are like the poles of a battery: hold them together, and they generate the energy of life; pull them apart, and the current stops flowing. When we separate any of the profound paired truths of our lives, both poles become lifeless specters of themselves, and we become lifeless as well.“

For us to achieve peace within ourselves and in the wider world, we need accountability.

We also need both memory and forgetfulness because if we cling too tightly to memory, and the anger and hatred it causes, it becomes impossible to find a path toward forgiveness, redemption, and peace.

Thank you again for being here with me today – and may we all find the ability to both remember and forget, to help us seek out our shared humanity with others, and thus repair our broken world.

Shabbat Shalom

[1] https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/zachor-why-jewish-memory-matters/

[2] IBID

[3] 1 Samuel 15:21